You can download the NodeSoftware as tar.gz at these locations:

Please see Upgrading.

The development repository resides at https://github.com/VAMDC/NodeSoftware and you are welcome to use the version control software git to check out your own copy. This takes a few more minutes to set up but has the benefit of facilitating collaboration. After all, you might makes changes or extend the code for your needs and we would like to include your improvements into the main repository.

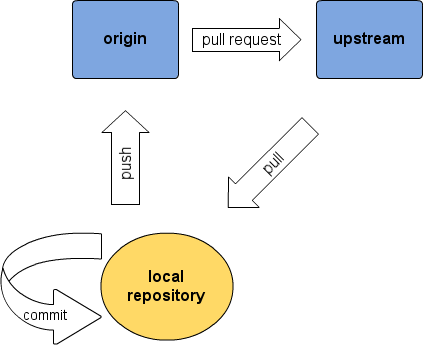

Git is a decentralized version control system (http://git-scm.com/). This means among other things that:

The setup that we want looks like this:

Now enough with theory, let’s do this in practice. To create your own repositories (origin and local) do the following:

Now that you are all set, a typical working session may look like this:

$ cd $VAMDCROOT # got to your local repo

$ git status # should tell you you have a clean tree and are on the branch "master"

$ git pull origin # pull from your origin, in case you pushed things there from another of your local repos.

$ git pull upstream # fetch the latest from upstream and merge it with your tree.

$ git log # read the commit log about what is new.

$ .... # edit your files

$ git status # review which files have changed

$ git diff # review details of your changes

$ git diff <filename> # see canges in one file only

$ git add <filename> # add a file to be commited with the next commit, e.g. a new file

$ git commit -a -m "message" # commit all changed files. ALWAYS check the status before you use -a to prevent that you commit unwanted files.

$ git commit -m "message" <filenames> # commit, but include only the named files in the commit

$ .... # more edits, more commits. until, at the end of day:

$ git status # also tells you how many commits you are ahead of your origin

$ git push # push all commits to your origin, also the new ones that came from upstream.

Note

There are several graphical user interfaces available for git that will facilitate overview and some operations for the less command-line adept. Commonly used ones for Linux are gitk and gitg. Good editors also integrate with git so that you can handle the version control from within the editor.

After you pushed your work to your origin, you can go to the GitHub wesite and send a pull request to the upstream repository, if you want your changes to be propagated to everybody else. We will then look at your commits and merge them.

A few dos and don’ts that are worthwhile to keep in mind with git:

Merge conflicts. When you pull from Upstream into your repo, other’s changes are merged with yours. It might however happen that someone else has changed the same line in the same file as you have in onw of your own commits, which results in a merge conflict. The pull commands warns you about this and git status shows the file in question as “both modified”. The file itself contains both versions of the conflicting lines, clearly marked. Edit the file so that only one version remains and remove the markings. Then you simply commit the file (and push).

Undo a commit. To undo a commit means exactly that, not that any of the files change. For example, undoing the last commit leaves you with as much uncommitted changes as you had before your last commit. None of your edits is reversed. Undoing commits is practical e.g. when you have committed too many things at once or unwanted files; or when you want to split one commit into several. You undo a commit with git reset –soft <REF> where <REF> is the commit that should be resetted to (i.e. the next-to-last one, if you want to undo your last commit). Common values for <REF> include:

Revert to an earlier version. If you want to throw away your edits since a certain commit, you use git reset –hard. For example, to revert all files to the state that they were in at the last commit (thow away uncommitted changes), you do git reset –hard HEAD. Similarly to the soft reset, you can also specify earlier commits that you want to reset to.

Look at an earlier version. You can check out any earlier version of any file at any time. For example, git checkout “master@{1 month ago}” <filename>” will give you the version of the file <filename> from a month ago. To go back to the latest, you do git checkout master <filename> (“master” is the name of the default branch where all you commits are). Note that the last command can also be used to thow away uncommitted changes in a specific file - a more gentle way than the reset described above.

You can also skip the <filename> to check out an earlier version of the whole repo (git checkout master brings you back to the latest). Instead of “master@{1 month ago}” you can use any of the <REF> mentioned above, or have a look at http://book.git-scm.com/4_git_treeishes.html.

Make a branch. Read git help branch for this.

One thing at a time. Please commit often and only include things in one commit that logically belong together. For example, changes to your node and changes to the common library should not be in the same commit but committed separately.

Meaningful commit messages. This goes together with the previous: If you cannot meaningfully summarize the changes you want to commit in onw or two lines, your commit is likely to be too large. Try to make the log messages meaningful!

Good code. Please try to avoid spaghetti-code, write modular, and follow http://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/

Pull first. Before you send a pull request, please make sure that you have pulled from upstream. This will make the merging of your code easier, since it will be you who needs to resolve potential conflicts before you push to your origin again.

The admin of upstream (aka the writer of these lines) might be bribed and/or convinced to turn a blind eye on violations against any of the above points, but he will be very happy if you try to follow them.

The following is the automatically generated documentation from the source code. It lists and describes all functions, classes etc.